Editor’s Observe: This text has been up to date to mirror the variety of eating places a sequence will need to have for the brand new...

Quick-food staff rally for well being and security protections close to a McDonald’s in Los Angeles, in 2021. Mario Tama/Getty Pictures conceal caption toggle caption Mario...

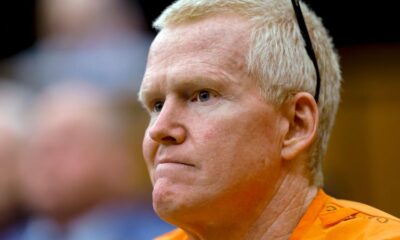

Charleston, South Carolina CNN — Convicted assassin Alex Murdaugh obtained one other jail sentence Monday, this time in federal court docket, the place a choose sentenced...

With two state jail sentences already on his shoulders, confessed and convicted fraudster Alex Murdaugh walked right into a federal courthouse in Charleston Monday to obtain...

Information 2024.04.01 The Worldwide Brotherhood of Teamsters is proud to acknowledge April as Autism Consciousness Month. The Teamsters Union shall be celebrating the contributions that our...

PJ Washington was added to the Dallas Mavericks on the commerce deadline in an try and rectify an low season mistake. Washington has been a revelation...

Getting a Skims marketing campaign is the modern-day equal of incomes a star on the Hollywood Stroll of Fame. It means you’ve garnered the eye of...

Sabrina Carpenter’s gorgeous marketing campaign pictures for SKIMS have gotten the stamp of approval from her rumored boyfriend, Barry Keoghan. On Monday (April 1), the “Nonsense”...

Barbara Rush, the Golden Globe-winning actor who starred within the sci-fi horror “It Got here From Outer Area,” has died. She was 97. Claudia Cowan, Rush’s...

NEW YORK (AP) — Shai Gilgeous-Alexander made the go-ahead jumper from the nook with 2.6 seconds left, sending the Oklahoma Metropolis Thunder to the playoffs for...