Ryan Guzman as Eddie and Oliver Stark as Buck in ‘9-1-1.’ Disney/Chris Willard Even 9-1-1’s Oliver Stark has to agree that his character, Evan “Buck” Buckley’s...

Your morning to night skincare routine ought to change as per the atmospheric temperature you’re uncovered to. What you apply in your face should match the...

Amanda Seales is opening up about her relationship with former co-star Issa Rae. Seales, who starred with Rae on the HBO dramedy “Insecure,” addressed the rumored...

Customized packaging is a method to do that, and customized die reduce bins are a superb possibility for creating distinctive packaging that may set your product...

Of the 11 monetary establishments that issued spot Bitcoin ETFs in January 2024, solely two — Bitwise and VanEck — have pledged to donate a proportion...

Donna Kelce is sharing her excessive praises for Taylor Swift‘s new album, The Tortured Poets Division. The mom of Tremendous Bowl-winning athlete Travis Kelce lately informed Individuals journal on...

Introduction to Digital Remedy Digital remedy, also called on-line remedy or teletherapy, has emerged as a revolutionary strategy to entry psychological well being assist conveniently. With...

VALERIE WATSON AND HER HUSBAND, RYAN WENT TO TURKS AND CAICOS TO CELEBRATE A 40TH BIRTHDAY. THEY WERE SUPPOSED TO BE HOME ON FRIDAY, APRIL 12TH,...

Italy, famend for its wealthy historical past, beautiful delicacies, and vibrant tradition, isn’t solely a vacation spot for vacationers but additionally a big hub for worldwide...

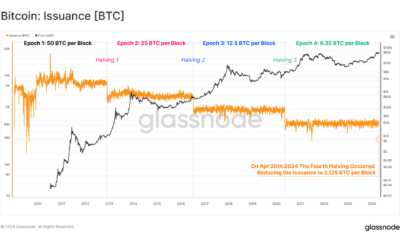

Following the newest Halving, Bitcoin’s inflation charge has formally develop into decrease than Gold’s, making BTC the scarcest asset in historical past. Bitcoin Halving Outcomes In...